(1)Megamergers Boost Healthcare M&A to New High

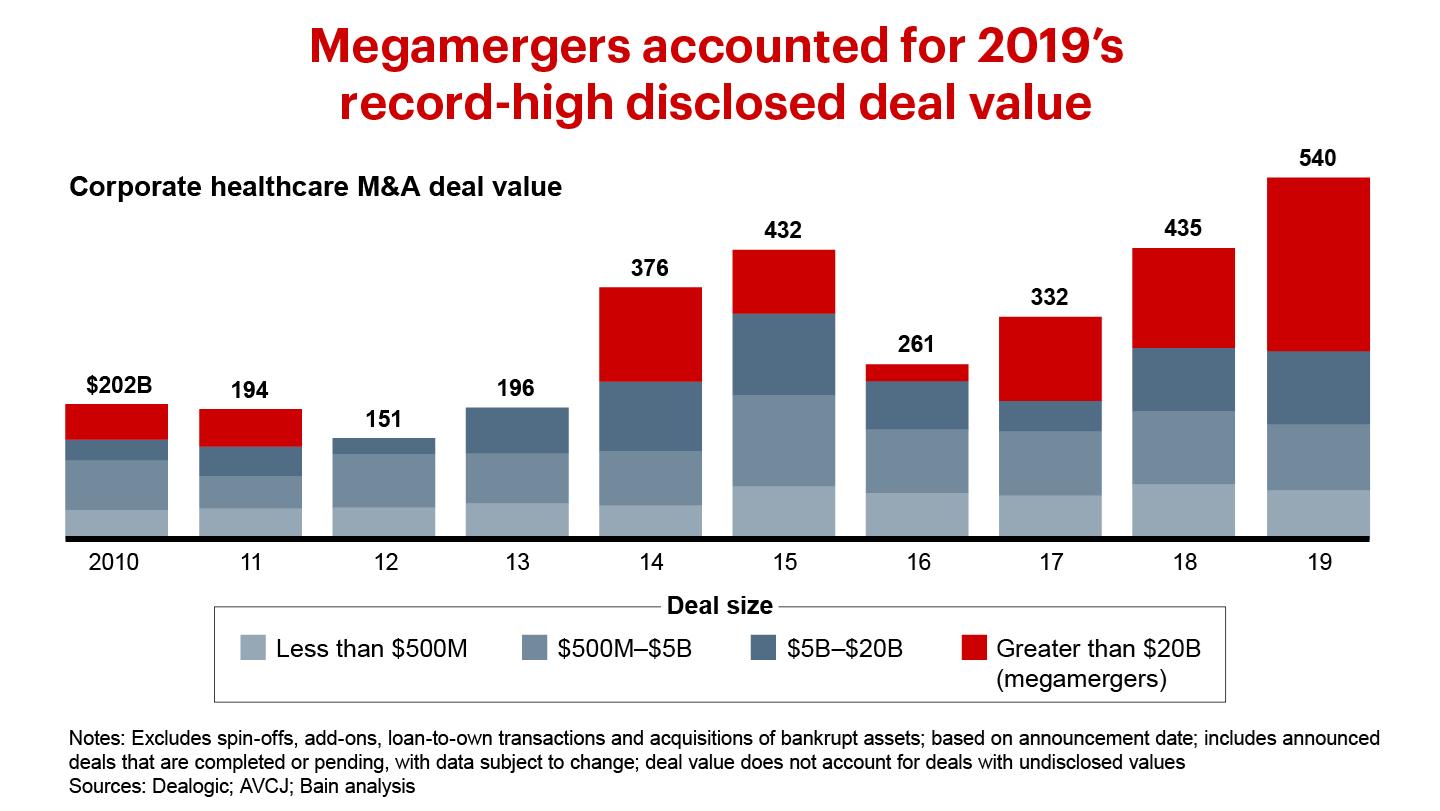

The disclosed value of healthcare corporate M&A rose by 25% in 2019, to a new high of $541 billion. Two megamergers—namely, Bristol-Myers Squib acquired Celgene, and AbbVie bought Allergan—totaled $182 billion. We expect brisk deal activity to continue in the near future as public healthcare companies use acquisitions to grow revenue, which public markets continue to reward differentially relative to profit margin expansion. New Bain & Company analysis of S&P Capital IQ data shows that revenue growth accounts for 62% of total shareholder returns over the past five years, a far more important factor than profit margin expansion, which accounts for only 9%.

(2)Healthcare Data Moves to Center Stage

From the heartbeat captured by a jogger's fitness tracker to the treatments at an emergency room, health-related data has been growing exponentially. Putting this data to valuable use and monetizing it has largely eluded most healthcare-related companies, though a few have recently begun to capitalize on proprietary data.

Several other industries have already found ways to use data to create entirely new business lines and upend established markets. In movies and television, researchers once could obtain only ticket sales and viewership estimates. As more people streamed shows online, companies such as Netflix began to harvest new forms of data that showed how viewers browsed, when they stopped watching an episode and what they switched to—all of which allowed Netflix to eventually compete against traditional movie and TV companies.

Healthcare faces a similar disruption by new, data-intensive companies. To be sure, healthcare has more regulatory complications than most industries, including strict privacy controls, as well as a fragmented system of providers, payers and patients that impede the collection and sharing of data. Still, the surge of interest in data affords opportunities that can be assembled within a PE portfolio. Potentially valuable use cases include the following:

·helping consumers make better decisions about healthy living;

·helping them find the right care and understand the true cost of that care;

·making care delivery more efficient for payers and providers;

·helping providers harness the power of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotic process automation;

·making clinical trials and R&D within biopharma more efficient;

·determining the commercial positioning of drugs through real patient data and evidence; and speeding up how a core business runs.

Where the value lies

Not all data will be equally valuable. What makes a data asset valuable for PE investors is a blend of several characteristics.

First, the data should solve an important use case, addressing a valuable pain point in some unique ways. While this may sound obvious, healthcare companies too often compile data without a clear purpose in mind.

Second, value lies in having a critical mass of data, so that it is solidly representative by being broad enough or longitudinal enough.

Third, the data should be unique or at least possess some proprietary aspect, through the data itself or a creative linkage of multiple sources, or through proprietary analytics.

Fourth, the data should be organized and structured such that it is easy to manipulate and analyze.

Finally, the data should come with access rights so that it can be shared with or sold to third-party organizations without violating privacy laws such as HIPAA controls on data sharing in the US.

Three promising business models

Healthcare's fragmented market, along with the strict privacy controls in many countries, makes it challenging to create longitudinal data that is sufficiently holistic, including clinical claims and pharmaceutical data.

Successful companies don't worry about building an elegant, perfectly scoped data set. Instead, they have improvised with scrappy, sometimes manual approaches to generate value from proprietary data. Companies are taking three promising tacks:

The core data provider. One option is to buy a traditional data company whose core business in its simplest form is to create and sell data. Such companies often have a beachhead of data into which investors can tuck other interesting data sources. Even when the data is not highly proprietary, its use and linkage to other data can make it valuable.

For instance, Advent acquired Definitive Healthcare, which has assembled and continuously refreshes a leading provider database incorporating links to other industry data, such as claims, that customers value for a range of uses.

The shape shifter. Other companies have realized that their core business is generating critical data that they could either use to transform their business model—as Netflix did—or resell for a different use case.

Flatiron Health, a healthcare technology and services company, illustrates this tack. Flatiron had an electronic medical records (EMR) platform designed for oncology care that touched 2.1 million active patient records as of 2018 and had longitudinal data. Pharma companies were interested in applying the data to several use cases ranging from smarter R&D to reducing control groups required in clinical trials. Because the EMR data was not clean, Flatiron invested heavy scrubbing to turn unstructured data—low-resolution PDF lab reports, audio files and digital copies of handwritten notes—into structured data. Once Flatiron completed the scrubbing, it could sell a unique data set that served a clear need at a specific customer phase within pharma oncology R&D.

The analyzer. A third option is to buy an analytics-oriented data company. Individual data sources may or may not be interesting commercially, but when pulled together and subject to proprietary analytics could yield rich value. Aetion, for example, serves as a bridge between pharma companies and payers, which need to agree on the real-world efficacy of a given treatment to support outcomes-based pricing agreements. Aetion's analysis provides a neutral and credible third-party perspective.

While the promise of healthcare data is intriguing, not all data has equal value. Due diligence should make a holistic assessment, including use cases and completeness of the data as well as whether investors can articulate the need for potential customers.

As data increasingly becomes top of mind for PE investors, there are a few things that best-in-class investors are starting to do:

·weigh the trade-offs of investing in a core data provider;

·assess the existing portfolio to understand hidden monetization opportunities or a business model that pivot data would enable;

·as part of diligence on new assets, think holistically about whether there is a data monetization play that could be made, or a business model pivot that data would enable; and

·do diligence on whether data could disrupt an industry, so that investors are not blindsided by a Netflix-like insurgent.

Investors will need to play both defensively and offensively in their data investments, and they should think expansively. Monetizing the wealth of healthcare data entails scrappy, hands-on work to polish data diamonds in the rough.

(3)Investors Must Consider the Effects of Healthcare Regulatory Reform

Regulation has been a key factor impacting the healthcare industry for decades. Although investors constantly assess the potential effect of regulation on specific investments as part of due diligence, we have not seen a material shift in investor behavior as a result of some of the recent regulatory rumblings, in part because of a belief in the continued positive macro fundamentals and increasing likelihood that new, game-changing regulations won’t be forthcoming anytime soon.

With that context, let's turn first to the US. In any US election year, issues of regulation and reform surface. With the November US presidential and congressional election, potential reforms span the payer landscape, drug pricing and other administrative and legislative changes, and are particularly relevant if a Democratic candidate and a Democratic-majority House and Senate are elected. Europe and the Asia-Pacific region also have ongoing regulatory efforts that could have mixed effects on investors. Let’s examine the US situation first.

US payer reform

Several federal-level reforms could come after the November elections. Most options would increase the number of people covered by government or government-supported plans and would be likely to result in some compression of rates depending on the specific plan enacted. Here is a rundown of key options: single payer, private insurance retained with a buy-in option, and reversal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

The single payer option

A single federal program for all US residents would replace private insurance and Medicare for covered benefits, though it probably would not restrict supplemental insurance for noncovered benefits. While much of the discussion has focused on a publicly paid, publicly administered plan, one option would use private insurers to manage the single payer program—akin to Part D, Medicare Advantage or Medicaid managed care. A single payer system would be the most disruptive option, but many view that option as not politically feasible. Possible effects on each sector follow:

·Payers: Single payer legislation would largely eliminate the need for private major medical insurance, including Medicare Advantage programs, outside of supplemental insurance, assuming that it is publicly administered.

·Providers: Providers would see a potentially substantial negative effect on prices, but potentially higher volumes and somewhat streamlined costs.

·Medtech: Most medtech companies would be affected indirectly as providers pass on costs to suppliers, though this will vary by product type. A single payer plan might also reduce the willingness to pay for innovation.

·HCIT: The fallout would vary by type of technology. IT that spurs efficiency might get a boost, depending on adoption. Other areas, such as the revenue cycle, would be negatively impacted, with an open question on any potential transition plan and the required technology to support this option.

Private insurance retained with a buy-in option

Private insurance with a buy-in option could be publicly or privately run. The publicly run version would be a federal health insurance option offered to eligible residents that competes with private insurance options—probably akin to the public option entertained during the Affordable Care Act debates in 2009–10. The privately run version would include buy-in options for all eligible residents, such as a Medicare buy-in to expand eligibility. Across all options, there is also a question on whether employers would be allowed to subsidize a buy-in for employees, potentially affecting the coverage of more lives. Possible effects:

·Payers: If the outcome is a Medicare buy-in, broadening the scope of privately run public plans, this could expand the opportunity for Medicare Advantage payers.

·Providers: Expanded coverage could mean higher covered volumes, with an open question on the rate impact depending on the chassis (private or public) and who is allowed to buy in. The consequences for rates are unclear.

·Medtech: There is some risk of derivative pricing pressure if providers are compressed. On the other hand, greater volume uplift from a newly insured population could benefit medtech companies.

·HCIT: There could be a positive effect given the added complexity of managing populations from new or expanded plans.

Reversal of the Affordable Care Act

The ACA increased access to insurance for those who were previously uninsured. It's possible that a Republican administration would further roll back many of these changes. Possible effects:

·Payers: If the ACA were repealed, payers with an exchange presence would potentially lose those patients and the associated margin (public data indicates that many payers are margin-positive on this population).

·Providers: The effect of volumes and rates would vary by specialty but would probably depress volume as more people are thrown onto the rolls of the uninsured. Hospitals would be likely to return to higher levels of uncompensated care.

·Medtech: There could be some risk of derivative pricing pressure if providers' profits get squeezed.

·HCIT: By contrast, HCIT firms would probably experience limited effects. Reversal might benefit patient-pay-focused solutions.

For biopharma, the question is tied up with separate drug pricing reform, although the sector could feel effects under a single payer scenario or as part of broader healthcare reform. A single payer model would most likely mean that the government plays a larger role in establishing rates, which would probably lower prices. Other options depend on what prescription drug reform looks like and the number of lives affected by the reform.

Drug pricing reform

Government officials have been discussing a number of options to reduce drug prices. The structure of future programs will hinge on several choices:

·Whether price increases will be controlled. The most likely option here would copy what already exists in Medicaid—the government recoups any price increases above inflation through increased statutory rebates from pharma companies. Democratic proposals have used this mechanism, including rolling back the past couple of years of price increases by backdating the baseline price.

·Whether list price will be controlled. The most extreme option here is international reference pricing, though that might not be feasible. A more likely route is statutory rebates off list price, again copying current Medicaid.

·Whether all branded drugs are affected. Some proposals (such as international reference pricing) apply only to the top 50 or top 250 drugs based on government spending.

·Whether the private market is included. One Democratic House proposal extends Medicare price reforms to the private market, so that private payers automatically get the same price as the government sets.

·Whether patient out-of-pocket spending is controlled. As is current practice, the main options are an out-of-pocket cap (either per prescription or annual), or moving to share rebates with patients by basing co-pays on the net price of the drug rather than the list price. The latter does not always require eliminating rebates; that is what the Trump Administration proposed for Part D, which it could do through administrative rulemaking rather than requiring legislation. If legislation passed, the rebate system would have a better chance of being retained. Anything that reduces patient out-of-pocket spending would have positive effects for pharma companies.

There is a range of possible effects on the biopharma sector. Severely negative reforms would include the imposition of European-style health technology assessment-based price caps, as well as the extension of government pricing into the private market. Reforms limiting patient out-of-pocket spending would generally benefit the industry.

In addition, a debate continues over drug importation, mainly from Canada. Importation comes with its own concerns, such as the security of the supply chain, and actions that manufacturers could take on drug prices in Canada to close the arbitrage opportunity.

Other potential US regulatory and administrative changes

Outside of major payer reform, other areas could see movement on reform, including some that do not necessarily depend on the outcome of the elections. Potential incremental reforms would have mixed effects on investment, although across all sectors, being on the “correct” side of the cost curve, and continuing the digital and data evolution in healthcare will be advantageous.

The efforts below represent a selection of reforms that are now under discussion, ranging from comprehensive (pricing transparency reform) to narrow (increasing scrutiny of the Institutional Review Board).

Surprise billing

This topic has been hotly debated over the past year. Reform of the unexpected charges that hospital patients face when they unknowingly receive treatment from a doctor who doesn’t accept their insurance would mostly affect out-of-network providers. In that situation, the rate billed typically exceeds in-network rates. Select provider specialties will most likely be affected, with minimal effect in HCIT, medtech and pharma. Depending on the final rule, payers may see modest increases in cost in the short term, but these are easily priced into premiums in subsequent years.

Pricing transparency

The federal government might require hospitals to display prices in a consumer-friendly format. This would include list prices that hospitals use as the charge master as well as negotiated, discounted prices that providers agree on with insurers.

While reform proposals have not yet taken shape, interest in transparency is mounting. Advocates argue it would promote competition and reduce costs as consumers gain the choice to move to lower-cost facilities and more providers compete on price.

While the concept makes sense, a few aspects make the execution difficult or nuanced:

·No procedures are exactly the same, which has allowed providers to justify charging different prices.

·In theory, transparency would lower overall prices across providers in a region, but some lower-cost providers might decide to raise rates to be more in line with higher-priced providers.

·Consumers don't always decide based solely on pricing. Insurance coverage and perceived quality matter as well. Historically, transparency tools haven’t achieved their penetration ambitions, raising a question on the ultimate effect of transparency, particularly for more complex services.

·Powerful provider health systems will continue to resist sweeping reform on transparent pricing.

Even absent step-change regulatory reform, investors should expect to see more results from public and private price transparency efforts, especially in consumer-facing aspects of healthcare, such as outpatient MRIs, where people can more easily understand prices. Companies in these markets that choose to introduce transparency even before a mandate might gain a competitive advantage.

Clinical trials acceleration

There has been a change in the FDA administration, and an open question remains on investment posture on clinical trials.

European reform

Except for harmonized centralized product approval processes, no common European reimbursement regulation exists. Rather, each social system acts on its own. Several legislative trends in Europe have a bearing on healthcare companies and investors.

In Germany, DVG, or the Digital Healthcare Act, will allow for a broad range of digital provision of care, such as telemedicine and online consultations or apps that help patients in recovery, to be reimbursed. That will fuel growth in digital health companies and make them more attractive investments.

In the UK, the main regulatory change in 2020 will come through the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework, which overhauls pricing and reimbursement for certain categories of drugs sold in community pharmacies, disrupting current profit pools involving manufacturers, wholesalers, community pharmacies and payers. The legislation will open the door for generic manufacturers to capture market share from branded drug manufacturers, and will squeeze the margins of some drug distributors.

While 2020 will be the year of Brexit in the UK, the effect on healthcare regulation is likely to remain limited. Statements by regulatory agencies suggest continued collaboration and alignment between the UK and EU regulatory regimes. The immediate effect on sectors such as medtech might be a need to ensure recognition by the European Medicines Association of dossiers that were submitted through the UK-notified body in previous years.

In France, a subsegment of the market will be affected by the 100% santé law of 2019, which aims to limit the level of an individual's out-of-pocket spending after the social security reimbursement. The state has also limited the prices for eyeglasses, hearing aids and dental prostheses.

In Italy, after years of drug price contractions due to government interventions, that trend has slowed and prices have flattened. No further drug price cuts are expected in the near term.

Across the EU, Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) and In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR) establish a higher data standard on devices approved for use. Key dates are May 2020, when the MDR regulation comes into force, and May 2022, when the IVDR regulation comes into force. Any new market entries will have to undergo the new procedure as of these dates, but could do so voluntarily before then. Noncompliant devices will leave the market at the latest by 2025.

The law has several implications for manufacturers. They will face higher operating costs over the next few years due to investments in data generation and regulatory advisory. They also risk having products taken off the market due to a backlog with the notified bodies, and potentially more complexity in executing clinical trials. Some manufacturers that have planned ahead could take market share, while others are using the occasion to prune their portfolios.

During due diligence, investors should understand the status of compliance for the product portfolio of potential targets, accounting for the costs that full compliance will entail. They should also evaluate whether being late to the game might force some parts of the portfolio out of the market. Conversely, there may be new investment opportunities in regulatory outsourcing organizations.

Asia-Pacific reform

Across Asia, regulators play an increasingly active role in addressing access, cost and quality constraints as evidenced by moves toward universal healthcare in China, Indonesia, India and the Philippines. Many regulators also recognize that digital solutions will be critical to care delivery, which shapes policy reform and raises the value of greater regulatory coordination.

China is in the midst of a multiyear national government reform to increase the quality and affordability of healthcare. A pilot program aims to accelerate the migration away from high-priced, off-patent branded drugs to generics though volume-based procurement. This program could dramatically reduce the cost of drugs through bulk buying in hospital systems, which are the primary distribution channel.

The program is likely to produce a winner-take-all outcome, and while prices will drop substantially, the winners will benefit from large volume increases. The next phase of these pilots covers medical devices and has begun to affect profit pools across the healthcare ecosystem. For investors, of course, this creates a window to identify and invest behind the winners.

In every region and country where regulatory change is underway, diligence and scenario planning around the probable effects of regulation will be essential to mitigate the risks and seize the upside opportunities.

(4)Asia-Pacific: Healthcare Private Equity Is on a Multiyear Growth Trajectory

·Healthcare investing in the Asia-Pacific region continued its sustained growth on the strength of aging populations, more chronic disease and rising incomes. Disclosed deal value reached the second-highest level since the past recession, at $11.5 billion in 2019. Buyout volume dropped to 68 deals in 2019 compared with 88 in 2018, due to declining activity in China.

·Investment was more geographically dispersed than in the past, as China, India and Australia represented 51% of disclosed deal value in 2019, compared with 90% in 2018. In particular, deals in Southeast Asia surged to 21% of disclosed deal value. The provider sector continued to see the most activity, with 29 deals and $4.4 billion of disclosed value.

·We saw three major investment themes: consolidating providers to execute buy-and-build strategies and achieve scale; investing in digital platforms and innovation to compensate for the gap in meeting the region's healthcare needs; and biopharma innovation as China looks to build out a local ecosystem.

Several trends have converged to put the Asia-Pacific region on a sustained growth trajectory for healthcare private equity. Aging populations, more chronic disease and rising incomes add up to strong fundamental demand. Governments are spending more, such as the universal healthcare initiative in the Philippines and Ayushman Bharat in India, and assets are attaining a scale conducive to private capital (see Figure below).

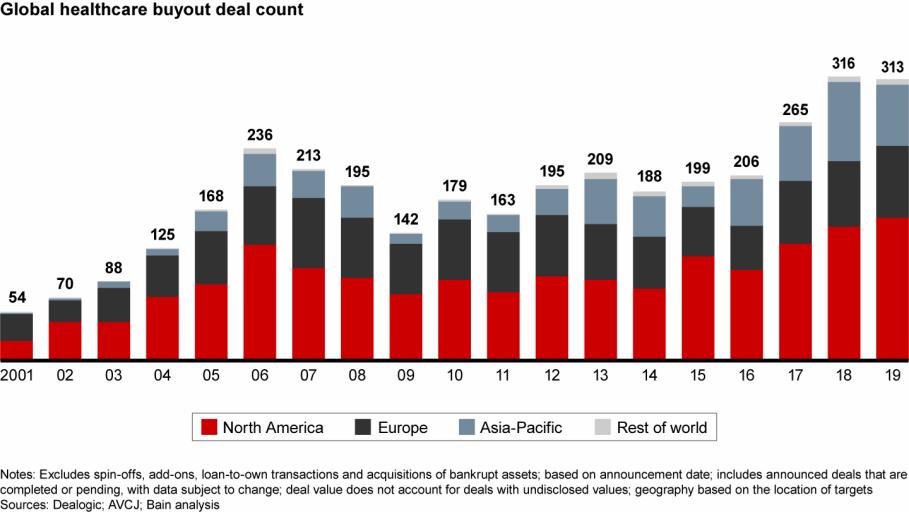

Deal activity increased in North America and Europe, offsetting a decline in Asia-Pacific

While total disclosed deal value of $11.5 billion in 2019 dropped from $16.2 billion in 2018, the 2019 level represents the second highest since the financial crisis. In addition, the largest acquisition of the past two years, Brookfield's $4.1 billion acquisition of Australian hospital provider Healthscope, was announced late in 2018 and closed in 2019, tilting deal value to 2018.

Compared with prior years, deal activity was dispersed more widely across the region. China faced geopolitical uncertainties and regulatory reform throughout the year, resulting in what should be a short-term dip in activity. Still, disclosed deal value was over 60% above its five-year average.

Looking across borders

Southeast Asia, which historically constituted a small share of the region’s deal value, expanded as assets reached the buyout sweet spot. Value increased from nearly $720 million to $2.4 billion in 2019. Southeast Asia saw the second-largest deal of the year in the region, the $1.2 billion acquisition of the Southeast Asian assets of Malaysia-based Columbia Asia Hospitals by a consortium of TPG and Hong Leong Group.

Investors continued to look across country borders to place capital, including assets that have a large exposure across the region, even if not headquartered in the region. For example, Baring Private Equity Asia made two notable investments with this profile. The fund acquired CitiusTech, an India-domiciled but US-headquartered HCIT platform that serves healthcare companies across sectors, for over $1 billion. Baring Private Equity Asia also bought Lumenis, a medical equipment manufacturer that sells laser equipment for minimally invasive surgery, from XIO Group, valuing the company at over $1 billion.

We saw a few key investment trends during the year:

1. Provider platforms with buy-and-build strategies

The provider sector continued to attract the most attention, representing 43% of deals in 2019 compared with 44% in 2018. Investors focused on consolidating hospitals and labs to execute buy-and-build strategies and develop scaled platforms. The private sector has stepped in to build hospital platforms where people lack access to care.

For example, KKR Asia and GIC Special Investments invested more than $684 million in Metro Pacific Hospitals, the operator of the largest private hospital network in the Philippines. In laboratories, TPG added to its Pathology Asia Holdings platform by acquiring a minority stake in Australian drug testing company Safe Work Laboratories.

2. HCIT and digital health

As a sizable gap in healthcare access persists across most of the region, physical infrastructure cannot be built quickly enough to meet the unmet healthcare needs. However, a propensity for digital adoption throughout Asian countries has allowed digital platforms to help address those needs, often with the participation of PE investors.

For example, CITIC Private Equity Funds Management, CICC Capital and Baring Private Equity Asia made a $1 billion investment in JD Health, an online pharmacy that is beginning to expand into online appointments and diagnoses, connecting doctors to patients in rural areas with little access to care. PharmEasy, an Indian digital pharmacy platform, received $220 million in an investment round led by Temasek Holdings that included a number of other funds and investors. And Halodoc, an Indonesian telemedicine platform providing doctor consultations and pharmacy services, raised $100 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, venture groups, Allianz and Prudential.

3. Chinese biopharma innovation with volume-based drug procurement

Underlying fundamentals make the sector attractive to investors. This is particularly true in China, where the government is investing to fuel a local biopharma ecosystem. Biopharma investments held flat at 17 in 2019, and deal values grew, despite uncertainty around the introduction of the Chinese national government's volume-based procurement pilot program.

In fact, the region's largest deal of the year was Centurium Capital's $1.9 billion take-private offer for the remainder of China Biologic Products Holdings, a plasma collection network and fractionator. The deal provides exposure to a profitable and rapidly growing industry in the plasma-derived therapy market. Outside of China, biopharma remains a promising area as well. For example, in India, Advent acquired Bharat Serums and Vaccines, a developer and manufacturer of specialized injectable medicine, from OrbiMed PE and Kotak PE.

Over the past several years, the Chinese government has been trying to increase the quality and affordability of healthcare. A pilot program aims to migrate away from high-priced, off-patent branded drugs to generics through volume-based procurement. This program could dramatically reduce the cost of drugs through bulk buying in hospital systems, which are the primary distribution channel. The program is likely to result in a winner-take-all outcome, and while prices will decline substantially, the winners will benefit from large volume increases.

In the first wave, 11 cities implemented a bulk purchase of 25 drugs, reducing some prices by over 90%. The second wave of the volume-based procurement program rolled out to the rest of China in the second half of 2019, leading to broader price cuts in off-patent drugs manufactured by foreign multinationals. We expect that Chinese biopharma companies will be best positioned to win the major contracts, which should lead to expanded investment in the near future. Longer term, Chinese companies might compete on the global stage in a fashion similar to Indian generics.

Poised for growth

Looking over the next five years or so, we expect several factors to have a big influence on healthcare in the region:

·An aging population. By 2025, 460 million people will be over 65 years old, with 60% of the growth in this cohort living in Asia-Pacific. They will require more health services.

·Rising costs. As healthcare costs rise faster than real wages, newer and more cost-effective delivery models could gain a foothold.

·Constrained physician resources. A recent Bain survey found that nearly half of physicians believe it will be more difficult to deliver high-quality care over the next five years due to lack of funding and resources, rising costs and a shift toward treating chronic patients.

·Consumer expectations. Consumers are frustrated with wait times, lack of affordability and other aspects of the care experience, which opens the door to solutions that can address these concerns.

·Technological and medical transformation. Asia-Pacific consumers have embraced digital tools, and digital solutions already are changing care delivery.

·Regulatory environments. Regulators have taken a more active role in addressing access, cost and quality constraints as evidenced by moves toward universal healthcare in China, Indonesia and recently in India and the Philippines. Many regulators recognize that digital solutions will be critical, which shapes policy reform and suggests a need for coordinating their programs.

Deal activity is likely to continue the trends of digital health, development of buy-and-build provider platforms benefiting from a fragmented and unorganized market, and a push into biopharma. We also expect cost and margin pressures to drive consolidation of smaller companies, particularly among providers.

Developments with the coronavirus, as of this report's publication, might create volatility in China deal activity in 2020. However, activity in China should pick up as regulatory reform flows through and if geopolitical tensions and virus concerns subside, particularly in biopharma, where Chinese companies are best positioned to win contracts in the future bulk-buying program. Interest in local Chinese medtech platforms could also surge as investors come to expect government reforms to spill into this sector, again benefiting local companies.